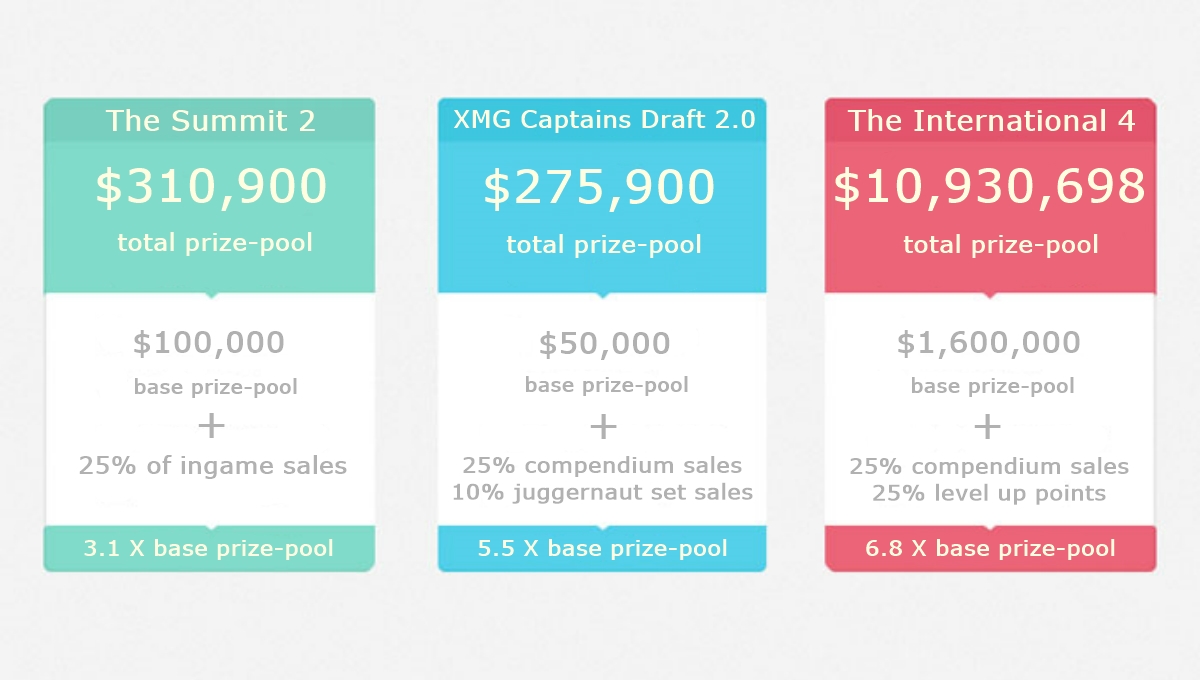

Last year, Dota 2 tournaments handed out over $16,000,000 in combined prize-pools. Quite staggering, isn’t it? The International 4 had a prize-pool of over $10 million – record breaking for the entire eSports scene, and more than 20 million viewers. Viewership is growing, sponsors are getting involved, cash is pouring in, and tournaments are flourishing. Things are looking up. Or are they?

In 2014, we had 32 premier tournaments raking in $15,088,600 in prize-pools, including The International 4 with its record breaking $10,931,100. On top of those, we had another 35 major tournaments, primarily online ones, with combined prize-pools of $673,310. Seventeen tournaments had prize-pools equal to or exceeding $100,000.

Most tournaments have started to increase their base prize-pools through crowd funding, raising monetary contributions from large key audiences. The concept, as applied to eSports, was first introduced by Valve for The International 2, in 2012, with the release of the virtual “compendium”. Since then, tournament organizers have been capitalizing on the success and community demand for items, to make additional profits.

In order to gain viewership and increased prize-pools, in-game tickets are sold. Bundle packages, sets for heroes, couriers, loading screens, HUD skins or item drops are often offered as incentives to purchase tickets. Compendiums provide a sense of “rarity”, with bonuses such as voting rights and fantasy line-ups. Better artwork and packages equals more sales.

While Valve maintains a permissive free market approach, not holding any exclusivity rights to tournaments, they do receive a portion of the sales and provide the license and approval for tournaments. Unlike League of Legends creator Riot, Valve has repeatedly voiced they do not want to be responsible for regulating tournaments.

Anyone with money or a plan can submit a request to Valve for an in-game ticket and workshop items to sell, then advertise and hold their online or LAN event. The process is relatively simple and open to all.

A free market is based on supply and demand, with little or no control or authority. While it allows for innovation, customer driven choices, and it makes industry access easier, it is often predisposed to failures when organizations look for short term profits and compromise quality, rights or conditions.

A free market paired with crowd funding in an unregulated manner is dangerous and detrimental to the quality and future of both online and offline competitions.

More and more tournament organizers ignore the ramifications of poor planning and cutting corners, and want to capitalize on the high monetary gain, instead of focusing on quality. This approach ruins the overall credibility of the Dota 2 scene, turning away teams, sponsors and viewers.

Dota 2 personality, Vitalii “V1lat” Volochai, stated in a recent interview:

The extinction of Dota2 will happen next year if things go on as they are. Any individual can announce a tournament, collect money and pay artists to create attractive items which will then earn huge profits and the tournament will be conducted online. Event organizers such as Beyond the Summit or StarLadder, pay approximately $100,000 to hold their LAN events and the profit is marginal if not negative. (…) Valve should regulate what level of tournaments can receive which or what level of items.

Dota 2 analyst and finance professor Alan “Nahaz” Bester said it best:

Free markets are not free. None I know of can function without infrastructure, oversight, and enforcement. (…) The kind of laissez-faire regulation that works when markets are small(ish) can fail disastrously when the stakes are raised. This is not about some tournaments being “good” and others “bad”. It’s about the incentives the system creates. Right now you can make a boatload of money by doing the absolute minimum to get an in-game ticket and then bundling it with some cool hats. There’s very limited incentives to actually have quality games or quality production, and even less to have LAN events, which many people believe are important to the ongoing growth of the scene. There are a LOT of concerns about where these incentives are going to take us going forward.

What happens when unprofessionals try to milk the Dota 2 cash cow?

The Dota 2 scene has experienced a recent influx of unprofessional tournament attempts.

Fire outbursts, power outages and 100+ ping in game at a LAN event does no justice to the scene

Self-advertised as “the biggest Dota 2 event in Southeast AsiaDay”, the Major All Stars tournament was organized by four friends who quit their marketing and advertising jobs, none of which had any experience in event coordination or tournament hosting. Needless to say, the tournament’s first day was a total faux pas: scheduling issues, delays, lack of casters in game, equipment not meeting the system requirements to run stream programs, microphones and equipment overheating, players hearing casters over the PA system, multiple disconnects during games, 100+ ping in game, fire outbursts and power outages in booths, broken PCs, tight team spaces with poor air ventilation. Basically, anything that could possibly go wrong actually did.

Lack of attention to details creates the impression of “scammy” business

CGUnited‘s plans for a large scale tournament of $500,000, were leaked before they were able to get their license approved by Valve. The event was supposed to be held in June, in the US. Once the community was on to it, a quick look at the company’s under construction dummy website had a ripple effect. The entire story had “scam in progress” written all over it. The company then announced pushing back the tournament until late September-October, 2015. The original website has been taken down.

Taking money from the crowd and having nothing to show for it

Synergy League advertised their base prize of $50,000 would be increased by $2.50 for each $9.99 ticket bundle sold. By October 2014, the total prize-pool had reached $57,000. As the online portion of the league was concluding, teams began to withdraw from the tournament for various reasons. Syngery League notified the remaining attending teams that LAN finals would be postponed. The official announcement was made on the tournament’s official VK page, stating that the rental for the venue was higher than expected, and exceeded their budget. The tournament was left hanging. The Synergy League website is no longer available and there has been no news or updates since. The crowd funded portion of the prize-pool has not been refunded.

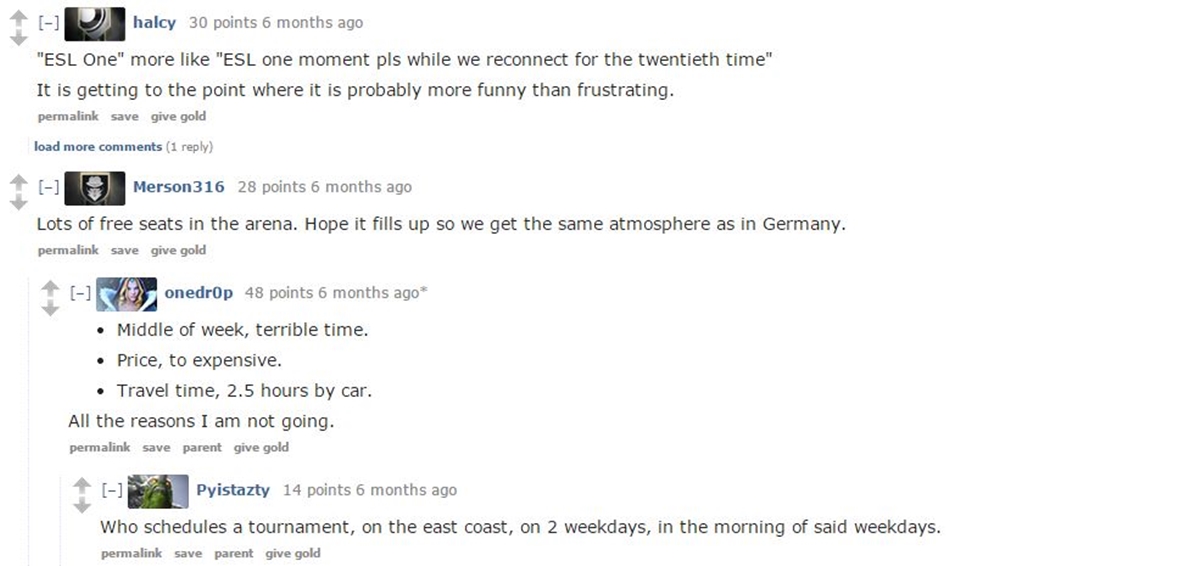

Bad scheduling, little if any market research

It also happens to the best of us. ESL hosted their first Dota 2 tournament with a $200,000 prize-pool LAN, in Germany, June 2014. Aside from having some minor issues in scheduling, things seemed to go smoothly. They then opted for a second tournament, at NYC’s Madison Square Garden, in October. The event was held mid-week and the tickets were expensive. Unsurprisingly, the venue was half-empty. For someone unfamiliar with the scene, that might convey the false idea that there is no interest for Dota 2 in New York and its surrounding areas.

Dota 2 enthusiasts took to Reddit to discuss the ESL One New York LAN event

The future

Since online tournaments bring bigger and faster profits, LAN events might become obsolete. However, from a competitive standpoint, online tournaments are undesirable:

- potential network and connection issues, such as recent DDoS attacks

- ping discrepancies from region to region

- players and viewers lack the live thrill of the event

- online tournaments attract less viewers

- online viewership does not appeal to sponsors

Sponsors are unprepared for the eSports phenomenon in general, and for the chaotic Dota 2 scene in particular. Let’s take NESCAFÉ, for instance. With no previous eSports experience whatsoever, they decided to sponsor a Hearthstone tournament, in April 2014. They’re now sponsoring their third Hearthstone competition. Would they have continued spending their money, had the first attempt proven worthless and unprofessional?

With the direction of tournaments and the future of the game at stake, it’s a crucial time to examine the available options. Numerous Dota 2 personalities have made public statements about the need for intervention and regulations through some type of organization or association. China and Korea are light-years ahead in this matter.

If nothing is done, the quality of tournaments will continue to decline, the amount of unprofessional events will increase, sponsors will run like stink.

It’s time to realize the elephant in the room, and stop milking the cash cow.

Photo: Glenn Sapaden

3 Comments

dpdvdl

(5 comments)this is nothing new to the eSports scene. as no 1 company can be held responsible for every tournament event, fingers will be pointed around blaming this or that. viewers will put stress on known and unknown companies to perform at a quality like The International, but the market may not be as strong in certain areas. i remember ESL One in NYC and how difficult it was to watch. the echo of the casters in the theatre was prominent despite us Eastcoast-ers finally getting a LAN tournament in our beloved city mid-fucking-week.

besides the misgivings of a tournament, there is hardly any solidarity in a team besides the name. i will like a line-up and cheer my goddamn head off for them, and a month later it’s 2/5 the same with the 3 others wandering off to a or 2 or green or school.

with Amazon having bought Twitch, i wonder if advertisers will piggy-back on to the eSport scene much in the same way that Google uses You-Tube. certainly a constant influx of $$ coming from a sidebar ad for the host(s) that could [hopefully] go to a better quality/performance of a tournament…pending hosters leech-like status.

anyways, thank you for the article above. glad to see it and know that it’s not just my own brain having gripes about the current Dota 2 eSports scene.

June 3, 2015 at 7:36 pmAndra Ciubotaru

(64 comments)Let’s hope proper roster locks will be indeed enacted. As for the current state of the scene, as much as I hate to say it, fish rot from the head down.

June 3, 2015 at 11:29 pmnemmdd

(57 comments)Its really interesting reading old article and comparing to current scene now.

March 11, 2016 at 9:02 am